About four years ago I came across a blog called "

The Power of a Passion." It was the product of a young chef who had recently moved to Miami after working in Chicago – first a brief tour of duty at

Alinea, then a year and a half at L2O during chef Laurent Gras' tenure, followed by a stint as pastry sous chef at

Boka, then a move to executive sous chef at

Epic. He'd come here to take a position as sous chef at

Azul restaurant, where Chef Joel Huff had recently been put in place as executive chef.

The author was Bradley Kilgore. And it may have been those blog posts as much as anything that prompted our interest in doing a

Cobaya dinner at Azul – one which ended up being filmed by Andrew Zimmern and featured in an

episode of Bizarre Foods. Anyone who was at that dinner – which included at least one course that was

Brad's creation – could sense that Kilgore had some real talent.

[1]

Several months later we made a return visit to Azul; Huff was gone and the kitchen was now in the hands of Kilgore and chef de cuisine Jacob Anaya. We gave Brad free reign and he put together a

sensational meal. His "

anatomy of a suckling pig" remains one of the most epic pork-fests I've ever experienced.

Shortly after, Kilgore got an opportunity to run his own spot, and opened Exit 1 in Key Biscayne. But for a lot of reasons that didn't work out. The location was far from ideal, the owners were not exactly veteran operators,

[2] and while Brad could cook, he may have been a bit inexperienced himself in all of the other components involved in running a restaurant. That didn't last long, but a better opportunity rolled around when he took over the chef de cuisine position at

J&G Grill in Bal Harbour. Here was an established high-end restaurant in the empire of one of the most successful restaurateurs in the world (Jean-Georges Vongerichten), with the bonus of getting to team up with one of Miami's brightest stars: pastry chef Antonio Bachour. Sure, Brad was mostly executing Jean-Georges' best hits, but he also got a little bit of leash to do his own thing too, including some really exceptional

on-request tasting menus.

So I was a bit surprised when last November, after a little more than a year at J&G,

Kilgore announced that he was leaving to open his own restaurant. As talented as I knew him to be, I'll confess I was concerned that it was too soon. The last thing I wanted – for him, and frankly, for myself as someone who really enjoyed eating his food – was another exit like Exit 1.

I was wrong. He was ready. And his new restaurant –

Alter, in Wynwood, which opened in late May – is already one of the best restaurants in Miami.

[3]

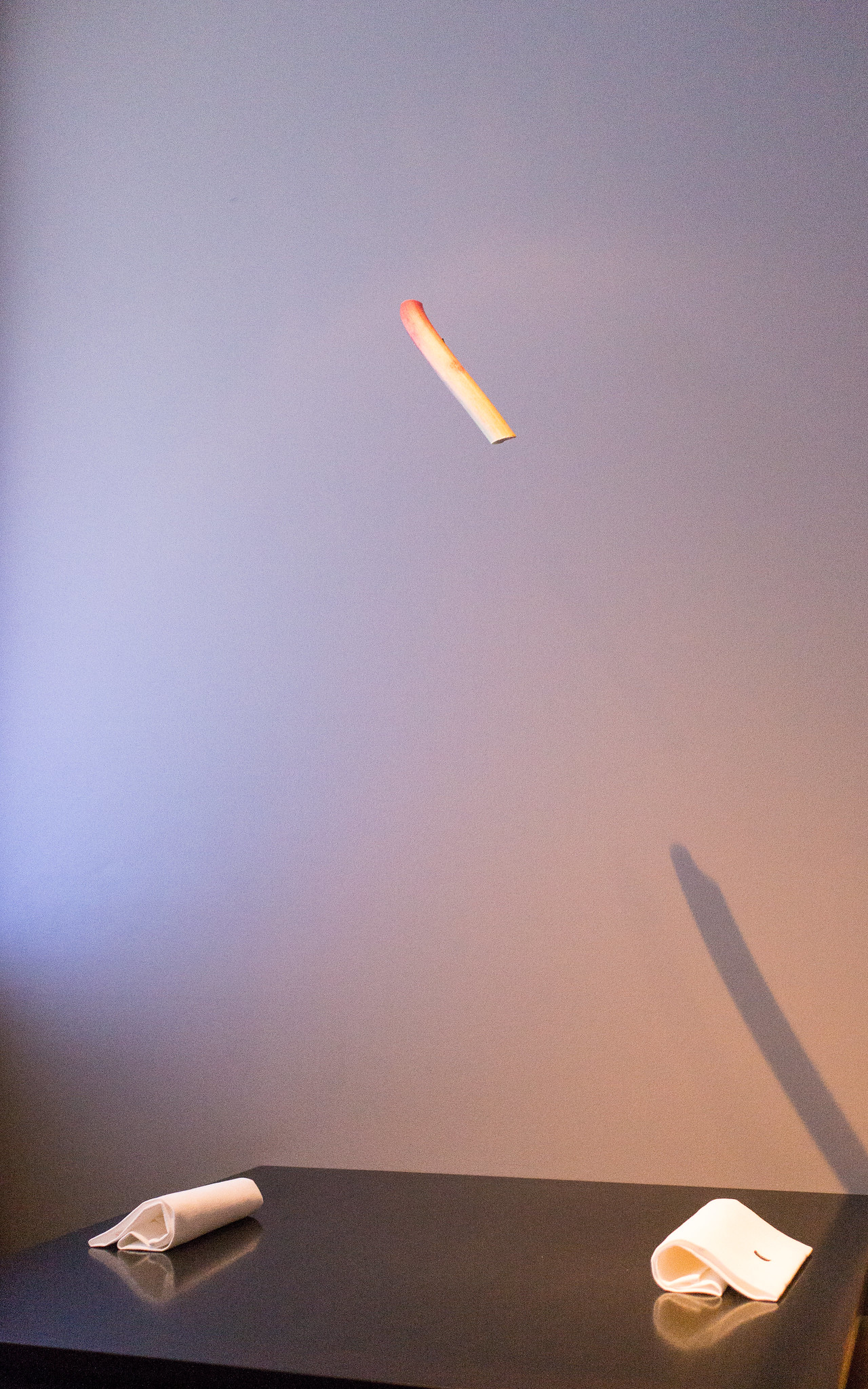

(You can see all my pictures in this

Alter - Miami (Wynwood) flickr set; pictured at top, a pre-dessert of assorted local tropical fruits in a crisp candy shell, served on an inverted woven palm frond basket).

The space, in the burgeoning Wynwood arts district,

[4] has a minimalist, industrial feel: the cinder block walls are bare, the ductwork is exposed, the primary decoration is an abstract squiggle of hot pink neon hanging over the liquor shelf that separates the open kitchen from the dining room. The dark-stained wood tables seat about forty, with a small extra seating area outside if the temperatures ever drop. The room can get too warm when it's crowded and too loud when the music's cranked up, both of which are frequent occurrences.

The menu is nearly as spare as the decor. There are usually about eight appetizers and a comparable number of main courses; a five-course tasting menu ($65) is composed from the kitchen's choice of several of those items, some in shrunken-down portions, and is both a solid value and a particularly smart option for a first visit.

Lots of places have fish tartare on their menus these days. Nobody has one like this. Multi-hued batons of green mango and various radishes form a haystack on top of precisely diced fish, the exact species of which is dictated by whatever is local and fresh. There are celery leaves,

[5] there's dried soy, there's yuzu kosho, there's black lime zested over the top. It's simultaneously spicy, citrusy, smoky, green, and fresh, as the flavors ping-pong between suggestions of a Thai pok-pok salad and a Peruvian ceviche and other things entirely.

A "signature dish" can be both blessing and curse. It helps define a style – and bring customers in – but can also be a sort of trap, something that can never come off the menu. Alter's soft egg may be its signature dish, and I'm sure it's much too early for Brad to be worried about golden handcuffs.

[6] A fluffy, brûléed scallop mousse, bearing just a subtle whiff of the ocean (turn up the volume with an optional dollop of Florida caviar), blankets a runny-yolked, soft-cooked egg hidden within. Also suspended underneath the surface are truffle pearls and a crackly shard of gruyere cheese, like those crusty bits on the side of the bowl that are maybe the best thing about French onion soup.

As signatures go, this is a fitting one for the cooking at Alter. The dish – like much of Brad's work – is a deftly executed balancing act between delicate subtlety and outright indulgence, earth and ocean, creamy and rich without being heavy and cloying. It also displays another thing I see often in Brad's cooking: the incorporation of dessert techniques into savory dishes, what with the mousse and the brûlée, inverting the past decade's trend of incorporating savory elements into desserts. Pro tip: if you're getting the egg, you really also need to get the "

bread & beurre," a tender-crumbed miniature loaf crusted with sumac and dill seed, and served with whipped, shoyu-bolstered "umami butter." The bread is delicious on its own, but as a tool for getting every last bit of the egg, it is particularly effective.

Summer squash is often among the most nebbish of vegetables. Not here. Zucchini and yellow squashes are cooked just enough to temper their bitter, raw edge, but not so much as to turn watery and slimy. A green circle of an herbaceous, dill-infused purée serves as the base for their arrangement, which is interspersed with dabs of tart, creamy lemon curd.

[7] Crumbles of soft feta cheese, a touch of citron vinaigrette, a tangle of crisp, fresh greens and some crunchy puffed wild rice complete the dish. It works a magical transformation on the squash, like a sexy librarian taking off her glasses and letting down her hair.

(continued ...)